|

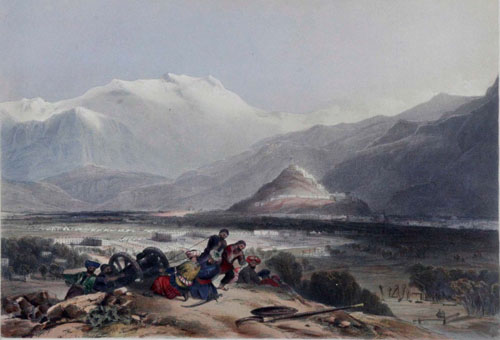

16. BRITISH CANTONMENTS AND CITY OF CAUBUL, FROM THE BE-MAROO HILL.

THE history of Afghaunistaun has been written in blood. Its capital has become a place of the saddest notoriety, in consequence of the utter disgrace and ruin which befel a brave and powerful army, induced by the inability shown by the leaders of it amidst a succession of unparalleled misfortunes. Many have been the pens, and right skilful the holders of them, to immortalize the name of Caubul. So much indeed has been said and written, that a further description would doubtless be treated as “a thrice-told tale.” Notwithstanding, I cannot abstain from briefly relating my first impressions of a spot, of which a portraiture, at once bright and dark, sorrowful and joyous, is deposited in my recollection, in traits so vivid as never to be effaced, so long as the troubled and uncertain stream of life struggles on, with its rocks and shoals, “up from the bottom turned by furious waves and adverse winds.” With this apology for entering a ground so often trodden before, a few words, ere I notice the details of the accompanying sketch, will suffice for this interesting city.

The Afghauns assert that Caubul is six thousand years old, and that the arch enemy fell there when driven out of heaven! The present city was built by the Ghuzneevide Sultaun Mahmood. It contains a population of sixty thousand people, and is six thousand four hundred feet above the level of the sea. It is well built and handsome, and is one mass of bazaars. Every street has a double row of houses of different heights, flat-roofed, and composed of mud in wooden frames. Here and there a large porch of carved wood intervenes, giving entrance to the court-yard of the residences of the nobles, in the centre of which is a raised platform of mud, planted with fruit trees, and spread with carpets. A fountain plays near; and here, during the heat of the day, loll the chiefs at ease, listening as they smoke their pipes to the sounds of the “sauringi,” or guitar, the falling water, or the wonderful tales of the Persian story-teller. The houses overhang the narrow streets; their windows have no glass, but consist of lattice-work wooden shutters which push up and down, and are often richly carved in eyelet holes, and otherwise ornamented, as in the picture of Dost Mahommed’s “dewaun-khaneh,” or audience-chamber, at Ghuznee. The shop-windows are open to the ground, and the immense display of merchandise, fruits, game, armour, and cutlery, defies description. These articles are arranged in prodigious piles from floor to ceiling; in the front of each sits the artificer engaged in his cunning, or from amidst the heaped-up profusion peeps out the trader at his visitors. The grand bazaar (Char Chouk, or Chutta), of which so much has been written, and at whose entrance the insulted and mangled remains of the late much lamented Sir William Macnaghten were hung up to the view of the whole Afghaun nation, has a substantial roof, built in four arcades, which are decorated with painted panels, now nearly indistinct, and originally watered by cisterns and fountains, which are neglected and dried up. In this building live the shawl merchants, who expose there their brilliant fabrics, or work at their looms. Here also reside the Bokhaura silk-venders, while furs and leather of Roos (Russia), chintz from Velayut (England), Peshawur kimkobs, Benares scarves, daggers matchlocks and armour from Isfahaun (Persia), Kybur “juzzails” and knives, Chinese ornaments, porcelain jars of rose-water, jewels, pictures, carpets and felts from Heraut, are arranged in such lavish profusion as to excite the utmost surprise and wonder. In fact, every article that the most fastidious taste required, for luxury or from necessity, was procurable. Other and inferior bazaars were covered in with matting, in which the fruits, flowers, game, and pyramids of ice surpass even the manufactures in variety and neatness. Each trade has a separate street, and the varied costumes of the busy throng of buyers and sellers lend their aid to render the scene charming. The bazaars occupied by drug, “tombauccoo” (tobacco), spice, snuff, and oil merchants, of whose stores the pungent assafœtida forms a material part, throw out a mingled odour by no means pleasant or grateful.

The streets are so narrow, that a string of laden camels take hours to press through the dense, moving, ever-varying crowds, who all the day long fill the thoroughfares. There are people from every part of the world. Pushing through the hot and thirsty populace, the water-vender, with his brazen cup and leather sack, finds a ready sale for his refreshing liquid. “Aub, aub,” he cries, “water, sweet water,” as he tinkles the metal basin with a small stick. Following him stumble a row of forty blind, sturdy beggars, asking alms and wailing in a monotonous chant, as they hold each other by the back of the neck or girdle, “the blind leading the blind.” Then come the ruwaush, or rhubarb sellers, with their merry cry of “ruwaush, Shauh baush ruwaush” (rhubarb, hurrah!) Old clothes-sellers and tea- dealers are there, each with his shout or call as nasal and prolonged as the stoutest pair of lungs belonging to a London fish-woman could send forth. In and out of the crowds, the women, in their shroud-like veils, thread their passage, or seek an easier plan of forcing it, astride on horseback. A ring of admiring auditors surrounds a Persian poet, who, while he recites verses, either his own or those of some favourite author, acts vigorously, and throws his listeners into all the variations of grief or passion. The multitude is suddenly pushed aside by a long train of foot soldiery, the advance guard of some great chief, who rides proudly on, followed by a troop of cavaliers, glittering in embroidered cloaks and trappings, and brandishing their spears and matchlocks. Taking advantage of the temporary opening in the mass of people, forward crowd, with cries and blows, the muleteers and horse-tenders, driving before them their mules, bullocks, and donkeys, laden with green clover and crisp bands of dried lucerne. After these waddle on the elephants of the Paudshauh, ripping at the tempting provender before them, tearing down with their monstrous flanks the outstanding water-pipes from the flat roofs, or backing into an ice or fruit shop, with loud shrill screams at the sudden approach of a horse round the corner. These scenes hourly, with camels and sheep passing and repassing in the narrow streets, where a horseman can scarcely turn without difficulty, render a passage through the Caubul bazaars a matter of inconvenience, if not of danger. Such was the never-failing variety of one of the finest bazaars in the East.

A few months rolled on, and I again entered this mighty city. Great changes and terrible had taken place in my absence. None of my former friends received me as before. Razed houses and blackened walls, once the abode of genius, hospitality, and rank, met my view. No one appeared―not even an Afghaun. The city was deserted, its habitations darkened and empty. We rode through the streets without encountering a living soul, hearing a single sound, save the yelp of a half-wild dog who had lapped up English blood perchance, and the echoes of our own suppressed voices and of our horses’ hoofs sent back through the long grim avenues of the closed bazaars. Our countrymen had perished miserably by the knife of the wild mountain tribes. The merchant forsook his loom, the husbandman his plough, and the artisan his cunning―trade was forgotten―the melon-bed and vineyard neglected; for all had risen as one man, and like blood-hounds on their track, had rushed, one and all, to revel in the gore of the detested and ill-starred foreigner. They fled and evacuated their city on our approach.

My want of space obliges me to conclude with a short explanation of the accompanying sketch. The Caubul force lay cantoned on a piece of low ground open to the high road to Coistaun, surrounded by a diminutive line of rampart, which formed a wall to the road itself. So low indeed was this misnamed defence, that a small pony was backed by an officer to scramble down the ditch and over the wall, which it accomplished easily. To the north of the cantonments (south-west in the sketch), and attached to them, was the Mission compound (the Envoy’s residence). It occupied an immense space, larger than the entrenched camp itself, and was surrounded by an indiscriminate mass of houses and buildings to officers of the Mission and the body-guard, and the whole square was encircled by the weakest possible wall by way of fortification. The three prominent squares above the scattered lines of the soldiery, stretching down to the Coistaun road, were the officers’ quarters; her Majesty’s 13th Light Infantry occupied the building to the extreme right, the 35th Bengal Light Infantry the centre, and the 37th Native Infantry that to the left, which flanks the orchards occupied by the generals and their staffs, in advance of the square of the Mission. The treacherous assassination of our Envoy and Minister took place on a slight eminence five hundred yards from the eastern rampart of the cantonments, or in the sketch, to the left angle of the 13th square. The cantonment was commanded at all parts by hills, forts, or other buildings; between it and the city, south of the former, is the unfinished magazine fort, and nearly opposite the south-west angle of the entrenched camp, the Coistaun road intervening, was Mahommed Naib Shurreef’s castle, commanding entirely that part of the works. Between our fortifications and the magazine fort was a bazaar and village which overlooked the defences on that side, and still nearer the city were our commissariat stores. To the east of cantonments was a broad and impassable canal, beyond which, issuing from the city, flowed the Caubul river in a straight line parallel with the Coistaun road. Several forts in direction also commanded most important positions, a few hundred yards from the doomed the cantonments; north of which was the village of Be-Maroo, near a low range of hills which bore the same name, and from which this sketch was made. It was on this hill that we lost our first gun, which was taken out without a second to support it. Tremendous was the slaughter in its defence, and unrivalled the courage of our brave troops, who were mown down in masses by the deadly “Juzzails” of the Ghazees, while they formed squares, by order of the Brigadier, to resist the distant fire of infantry.The name Be-Maroo (without a husband) is derived from a virgin who buried there.

It is not my intention to do more than attempt to describe the different points of interest in this sketch, nor have I space to particularize the features of the insurrection, the awful calamities consequent thereon, or the heroic deeds of the brave men, who, though they perished miserably while vainly striving to uphold their national honour, yet fought to the last with an intrepidity and devotedness worthy of the army they represented. Doubtless our subsequent annihilation may be ascribed in the first instance to the unaccountable absence of military judgment or skill, which selected such a position for an army in the heart of a half-conquered country; a cantonment that troops could neither quit nor enter without running the gauntlet of a tremendous fire poured into them from fortress, garden, village, hill, and wall, which hemmed in and commanded every face of the ill-contrived and widely-scattered lines. Should this rough and unsatisfactory account induce the kind reader with the wish to learn more of the heart-rending events of that period, I beg to refer him, with the strongest recommendation, to the truthful and deeply-interesting little volume entitled ‘Journal of an Afghaun Prisoner,’ by that brave and talented officer, Lieut. Vincent Eyre, Bengal Artillery, one of the few permitted to survive the annihilation of an army of upwards of seventeen thousand men. May he and his companions in misfortune and imprisonment live long to fight, in a happier cause, the battles of their country!

[Keywords]

sarangi/ chawk/ welayat/ kamkhab/ tanbaku/ ravish/ Bibi Mahru/ Sultan Mahmud/ diwankhane/ Ghazni/ Bukhara/ Isfahan/ Peshawar/Herat/ Kohestan/ jazayel |

NEXT

NEXT |

|

|

BACK

BACK |

|

|