|

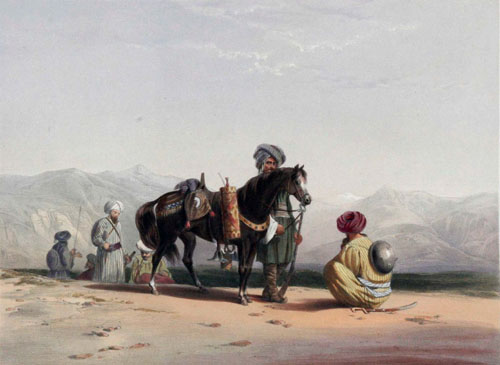

17. HORSEMAN OF THE JAUNBAUZ, OR AFGHAUN CAVALRY.

NEVER were a wilder, more devil-may-care set of fellows seen than the Afghaun cavalry, of which, regiments were raised for the service of the Shauh. They rejoiced in the characteristic appellation of Jaunbauz, “sporters with life” (or as Khooshhaul, a popular Afghaun poet, describes them,― “Men of spirit, who sported with their lives;” “They went to their graves dyed with blood :”)―and were to be disciplined by European officers. When levies were requisite, each chieftain brought in all those of his retainers, who owned a horse, sword, and gun, from three to eighty being produced for approval by each. They are often armed to the teeth in the most fantastic manner. All more or less robbers by profession and nature, they are soldiers when it suit them. When they take up the more honourable calling, they do not always consider it necessary to put off the old one. For instance ―they are paid according to the respectability of their outfit, and occasionally, when a horseman is rejected on account of the badness of his animal, he says, “Pray, Sir, take me, for I did not steal my nag, as those rascals did,” pointing to his comrades. Should this extraordinary profession of honesty fail of the desired effect, he adds, “Oh leave my place open, and Inshallah Ta-allah, please God I will return splendidly mounted and appointed in every way.” And this he is always sure to do. Though we knew these worthies considered it no sin “For those to take who had the power, And those to keep who can,” we never dared to insult their honourable feelings by hinting at the impropriety of their actions. These regiments were in fact composed of all the troublesome souls whom we wished to keep employed and out of mischief. Many of them were cut-throat looking dogs, mighty independent, and so loose in their morals, that whenever we had the luck to get worsted, they were never troubled with too strict pangs of conscience, but began to plunder the beaten party, whether friend or foe. They took our service because we paid them well and regularly, but a great deal of the savoir faire was required in the management of them. Being naturally a restless and independent people, and according to one of their own proverbs, ready to bear hunger, thirst, cruelty, and death, but never― a master, they, by the same rule, could not endure the discipline of our regulars. We found these mercenaries willing and serviceable so long as our good star was in the ascendant, but when our sun was temporarily setting they deserted from our ranks, and not only showed the serpent tooth of ingratitude, but murdered their officers in cold blood whenever the opportunity offered itself. Thus it was with the Jaunbauz cavalry commanded by Captain Golding. He was a most zealous officer, and universally beloved; and particularly popular even with his men, considering their relative position as Feringhee commandant and Afghaun hirelings.

In the latter part of 1842 this regiment and the 2nd Jaunbauz were called in from the Ghirisk frontier when the news of the Caubul catastrophe reached Candahar, and were encamped under the city walls outside the Heraut gate. But whether it was deemed imprudent that men of such questionable character should be allowed to remain on the spot, when each day ushered in long lists of fresh murders, butchery in the closet, and wholesale carnage in the field, of our best and bravest at Caubul; or whether the ridding us of their proximity was considered of sufficient importance to justify the sacrifice of their commanding officers (Golding and Wilson, with Pattenson, 2nd Grenadiers, Political Assistant). I cannot say. At all events they were ordered back to a distant station in the valley, where no help could have reached them in the event of a mutiny, which every one knew must follow such a step. On the receipt of this counter-order, the deep murmur of dissatisfaction immediately arose in their camp. A few days prior to this I was invited to a feast given by Golding to the Afghaun officers of his own and Wilson’s regiment, on the occasion of investing one of his officers, Kallunder Khaun, Caukur, with a dress of honour, or “Khellut.” He was a designing, evil-looking fellow, with a high forehead, and a continual twitch in one eye, which added to his bad expression. The banquet over, and the “Mobaurik Baushuds,” “may it (the dress) be auspicious,” passed on the honoured Kallunder, we rode out to cantonments.

On the following morning we met at the mess breakfast. It was Christmas day that had broken upon us, in the midst of sorrow, dangers, and difficulties, ―a day on which, instead of the “happy season to ye,” we received the inglorious Caubul treaty, heard reporters of the total annihilation of our troops, read the Hookm è Padshauh (the king’s order) to evacuate the country, and saw the interminable lists of our butchered brethren in arms. Sad and joyless were the light-hearted ones of our party, and the customary congratulations of season interchanged among us seemed almost a cruel mockery to our real feelings. Golding and Pattenson dined at mess, and we rallied each other on our melancholy looks. Golding rose at twelve p.m., and we grasped his hand with heartiest wishes for his speedy return to us, for his regiment was to march at down. He sighed, “Before we meet again the crisis will be over!” Was that the voice of a prophetic spirit? Or had he been warned of his approaching fate? This, alas! we were fated never to learn. We parted, Pattenson and Golding for their tent in the Jaunbauz lines, and we to our beds, which we had scarcely occupied, when at morning twilight we were all aroused by musket shots, succeeded by the shrill, fierce, fiendish howl, Allah, Allah, Allah, of the Afghauns. “Golding is carried off,” burst instinctively from us, and was echoed through the barrack’s long arcade. On rushing out, running and affrighted natives met us with “Golding has been murdered, Pattenson carried off, and their Jaunbauz fled.” On arriving at the ground, the combination of fearful sensations which crowded on me almost to suffocation can never be forgotten. There lay the still glowing ashes of their expiring watch-fires, the scattered provender, the marks where the horses had been tethered, and the impressions of the tent-walls in the sand, with other indications of a hasty flight. The sole representative of that once busy, merry camp, was a single dilapidated tent, out of which flowed a long ribbon of blood, marking the ground for many yards. Clots and puddles of the same dark liquid guided the horror-struck inquirer to the base of a slight undulation, where poor Golding had crept to die. His body was found lying in a pool of blood, hacked to pieces. On entering the fatal tent, where the unhappy victims could not have lain an hour, the ground was found cut up and torn by the heels and hands of the fearful death-wrestlers; the walls were splashed with gore; marks of bleeding palms, as if clutching the tent-sides for assistance, showed that the end came slowly, while a severed finger and a cloven wadded skull cap marked the fierceness of the dreadful straggle. Bullet-holes pierced the roof. These were the shots that aroused us ―fired as a feu de joie by the Afghauns at the success of their hellish work, accompanied by their shrieks of delight. Poor Pattenson’s fate was far more cruel; for, after receiving while in bed some fourteen dreadful wounds from sword and knife, he was borne from the tent by a faithful Herautee groom of Golding’s, who, taking advantage of murders being intent on plunder, to save his master’s friend, threw him naked, bathed in gore and senseless, on the back of Golding’s favourite Arab, and then binding him Mazeppa-like, cut the horse’s head and heel ropes. The noble animal fled instinctively into the city with his bleeding charge, who lingered on in a fearful state of excruciating agony for upwards of three long months, and died, poor fellow, after suffering amputation of his leg, a hand, and fingers, sensible to the last. It gives me sincere pleasure, though it be a sad and melancholy one, to mention here how universally these two brave and well-tried soldiers were beloved, and their untimely fate lamented. They were followed to the grave by the whole garrison, and many a comrade “wiped away a tear.” Their military career was short, though bright and glorious.

But we must not forget to follow up the feasted and honoured Kallunder, the traitor and the murder. He was not permitted long to boast of his horrid deed. We required blood for blood, and we got it! On the hue- and-cry being raised of the double murder (for we may call it so) regiments were ordered out to surround the camp. The cowards had fled to a man. Leeson’s 1st cavalry, and Wilson’s 2nd Jaunbauz, were forthwith sent in pursuit. They met several Afghauns, but learnt nothing satisfactory, until a horseman, whose movements were suspected, was stopped as he galloped past. On being questioned, he confessed there was a chief, who had murdered a Sahib, and whose cloak he was displaying, gone with a large body of cavalry to a village a little ahead, to collect footmen, and make a stand if attacked. On penalty of death he was desired to point them out, which he did. After riding on a little distance further, there they were, sure enough, all drawn up under a wall. Wilson and his standard-bearer charged alone, as the whole of the Jaunbauz refused to move. When these two had joined the 1st, the regiments advanced in line, but finding a wide deep ditch in front, they were obliged to cross over it singly, and re-form on the opposite side. Then the enemy began to move towards them, and after firing their matchlocks increased their pace to a trot, and from that to a canter. They had just mustered up a gallop, when “advance to the attack” was the order of the day, and “charge” immediately followed The Hurrah, with the names of Pattenson and Golding, was most exiting, and before it had ceased the mélée had commenced in right good style. The hard fighting lasted for five minutes before the assassins broke, which they then did in two bodies, in one of which the arch traitor was recognized, decked out in poor Golding’s gift, the dress of honour. On seeing him Wilson cried out, “A thousand roopees to the man who will bring me Kallunder’s head” (a sum this gallant officer paid down at his own expense, and was, I believe, afterwards refused compensation for it), on which he was assailed from all sides. He fought desperately, and had his horse killed under him. Besides other frightful wounds, he received a sweeping cut from a sabre, which laid his skull open to the brain, yet he would not give in, but setting his broad shoulders against a wall, stood there at bay like an infuriated tiger, dealing out blow for blow, and cursing horribly. He received the coup de grace at last, his death-wound nearly cleaving away his under jaw. His head was cut off, carried to the camp in a handkerchief, and there exhibited. It was afterwards lent to me, and I kept it several days to make a copy of it. It was a splendid study, that same skull, with its ugly gaping wounds and clotted beard; in addition to which its face, as in life, had the same bad expression fixed in death, even to the twitch in the half-closed eye, which seemed still to be winking in mockery at its deed of foulest treachery. Of Kallunder’s horsemen fifty to sixty fell, and among them two of his own relations. Of the wounded was the Sirdar Taj Mahommed, formerly commander of another Jaunbauz regiment, who, with other chiefs disabled in this fight, had deserted from us.

I have to thank my friend Lieut. Crawford T. Chamberlain for supplying me with the materials for the charge, and for the present (after its wonderful recovery from the wound) of a beautiful Gulph Arab, which bore him on that memorable day, and was nearly cut in two in the affray, from the sweep of a crooked blade across the hind quarters. He, his brother, and Wilson fought under Capt. Leeson on that occasion, and where such men were it could not be doubted that the happiest success was certain to crown their gallant efforts. The horse in picture bears a pan of live coals slung under his girths for lighting the “Kulleaun.” At the saddle-pommel hangs the “Kulleaundaun,” or box for pipe, and smoking apparatus. The saddle rises high on the horse’s back, and is peaked in front and rear; it is small and confined, the seat hard and uncomfortable, and the pommel peculiarly well adapted for an empalement. The stirrup is formed of a long flat piece of narrow iron, or a bar like our own. Plain cloth, or embroidered housings of velvet or gold, according to the degree or taste of the owner, with fringed borders, reach from the saddle to the horse’s tail, and give a smart appearance to the animal. Saddle-bags of carpeting are always carried. The reins and bridle are adorned with studs of silver or iron, and the breast-band with one or more knobs of the same material.

[Keywords]

Janbaz/ Kakar/ qaliyandan/ Khoshhal/ Farangi/ Kabul/ Qandahar/ Herat/ Qalandar Khan/ khil‘at/ Hukm-e Padshah. Herati/ Sardar Taj Muhammad/ qaliyan |

NEXT

NEXT |

|

|

BACK

BACK |

|

|