|

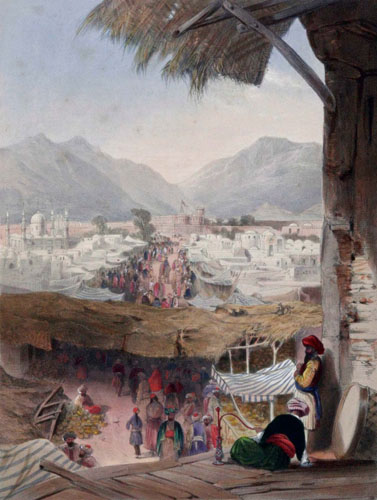

28. BAZĀR AND CITADEL, FROM THE ROYAL BAND ROOM, CANDAHAR. 28. BAZĀR AND CITADEL, FROM THE ROYAL BAND ROOM, CANDAHAR.

THE Nakarra Khana, from the terrace of which this representation was made, is the room where the royal band plays. It is situated in the very centre of the city, in the domed building called the Charsoo, under which is a covered space where the proclamations and public orders are read; where the best shops for arms, books, “Cullumdauns” (pencases), and every variety of Persian goods and merchandise are to be met with, and where also the limbs, heads, and trunks of malefactors are hung up for exposure to the public gaze. Nothing can surpass the wild, stunning, and unearthly music of his Majesty’s band, issuing from this quarter of the city. The performers attempt only three to four notes, repeated in regular rotation on a dozen deafening drams, discordant horns, and hoarse speaking-trumpets, from the most dismal bass to a high braying treble, the whole burden of their strain being “Shauh Shujau, Shau---uh Shu-jau.” The first time that my ears were regaled with this barbaric melody was at morning twilight, during a deep snow at Jellulabad, the winter palace of the Shauh, when it suddenly clanged forth so unpleasantly near (though somewhat deadened by snow, tent walls, furs, and bed covering,) that I was obliged to wake up my host, before the morning cup of tea, in mercy to tell me the worst. He comforted me with the announcement that it was only the King’s crack orchestra, and further, that I should have plenty of that if I lived long enough. Truly the Afghauns have no music in their souls, however much they fancy they possess in the voices of their speaking-trumpets; though I once heard the guitar played passably well in the grove of Jugdulluk by one of them. The Shauh himself, on being invited to hear one of the full regimental bands, remarked it was well (Khoob bood), but would bear no comparison with his own, which spoke music. The Nakarras, whose reverberations for miles around proclaim the entrance and exit of the Sovereign and Princes, serve likewise to tell the divisions of the day, as they play at daybreak, midday, and midnight. After that hour till the morning beat, no one can appear in the streets on pain of imprisonment and fine.

The bazār, extending on this side from the Charsoo to the citadel, was always a gay, thronged, and ever-changing scene, and from midday was crowded to suffocation with wild tribes and people as various and extraordinary as the wares they are engaged in purchasing. The thousands of heads, wreathed in huge turbans and rolls of silk or linen, “and the sparkling sheen Of arms,” (in the East all arm,) “and various dyes Of coloured garbs, as bright as butterflies,” looked down upon from a height, produced a gorgeous and singular effect. Among sweetmeat, ice, delf, earthenware, cutlery, fur and shaving shops, delicious fruits of rare kinds were to be seen in perfection, not only hanging from the ceilings of the houses, but piled along the verandahed streets; while pomegranates, melons, figs, and “showering grapes In bacchanal profusion reeled to earth, Purple and gushing,” among every possible variety of purchasable article, ranged carefully in tiers on either side the way, which was broad and handsome for an Oriental bazār. The lofty and spacious edifice which we pass on our left from the Charsoo to the citadel, with its polished cupolas, and “white walls shining in the sun,” forms a pleasing contrast with the wooden-framed houses of red and unburnt clay. It is a mosque, sacred by reason of the enshrinement therein of the Prophet’s shirt. This relic was guarded by us with great care, for Atta Mahommed, the great Douraunee lord, had well-nigh succeeded in stealing it, in order to employ it as a banner for the encouragement of his fanatic army in the holy war against the Feringhees. The interior of the building was somewhat similar to that of other Musjeeds. Its walls were covered with texts from the Koraun, ―“Soft Persian sentences, in lilac letters, From poets, or the moralists their betters.” Beyond the citadel and ramparts is a plain, bounded by a mountain range, whose rugged outline appears above the walls. Its name is appropriate, Kootul-i-Moorcha, or pass of the ant. It is so called from a defile through its centre, so narrow and precipitous, that a horseman, ambitious of passing between its perpendicular walls in an uncrushed state to the valley beyond, is under the necessity of dismounting. To the front of the same fortification is a square occupied by our park. Here, after dragging the two eighteen-pounders to the entrance of the Charsoo to sweep the street leading out of it to the Heraut Gate, we were drawn up to make our last stand, in case the well-planned attack of the besiegers, on the night of the 10th of March, had proved successful. Here, too, the Douraunee chief, Ukram Khaun, was blown away fro m a gun. The heart sickens at such butchery perpetrated on an innocent man, or at the least guilty of no other transgression than that of fighting for his own country and household gods.

Candahar was a royal residence, as Timoor, eldest son of the Shauh Shujau, dwelt there as nominal governor. I often paid my respects to him. His royal highness was a handsome, grave-looking, and highly-respectable man, of retired and studious habits, and bore the character of a strict Mahomedan. He moreover possessed but one wife, and preferred quiet and seclusion to the pomp and cares of royalty. Of pleasing and princely address, with the deep rich voice of his father, whom he resembled likewise in his olive-complexion features (except their scornful expression), and long black beard, he was the model for a Prince of the house royal. We found him usually seated in his gardens, near a fountain fed by a piece of water covered with varieties of wild fowl, round which were walks and flower-beds laid out in trim though quaint fashion. When I paid him my last visit, he sat in his favourite spot, book in hand, and his sons, two beautiful boys, with bright red cheeks and black eyes (who, he complained to us, preferred, very naturally, we thought, riding and field-sports to studious pursuits), were playing around him. The little urchins were fully armed with sword and dagger; indeed, they were in dress their father in miniature, except that they wore the full-sized man’s turban, instead of the crown. The Prince was attired in a lilac satin tunic, and white Cashmere shawl girdle: on his head was the black velvet hat, shaped like a turn-cap lily, with jeweled gold band, and emeralds pendant from the four leaves curving downwards from the crown. He spoke somewhat bitterly, though composedly, of his changed fortunes, for he had just heard of the murder of his father, and the report of our intended evacuation of the country. As we passed from the presence, his “Nakarras” struck up; those drums were the knell of falling greatness.

Before leaving the subject of Candahar for ever, I cannot refrain from mentioning one among many happy recollections of life in barracks there―a circumstance to which, I feel convinced, the army at large will respond with pleasure equal to my own. It was the addition to our little force of H. M. 40th Foot, a fine regiment, whether regarded on the parade-ground, on the battle-field, or in the more social duties of private life. Always as a body in splendid order and discipline, the officers were individually hospitable, gentlemanly, and agreeable. Pleasant were our meetings at mess and bivouac. Many, I deeply regret to add, have passed away since those stirring times, among whom I lament two friends in particular, Colonel Hibbert, C. B., and Lieutenaut Seymour; but I trust the gallant survivors will receive kindly, as it is meant, this humble tribute to their numerous merits.

The concluding portion of this chapter I shall devote to a few random remarks on the national claim of the Afghauns to a Hebrew lineage, acknowledging at the same time that it looks like great presumption on my part to venture on ground so difficult and intricate, or even to touch on a matter which has been discussed over and over again by some of the most accomplished scholars of this age, without anything being ascertained beyond a doubt of their real origin, or their title to call themselves Bin-e-Israueel, sons of Israel, a title founded on their alleged descent from the ten lost tribes. Nor have I anything new to advance in favour of such a supposition, and wish merely to state what I have heard broached on the subject by the Afghauns themselves, and by my particular friend Captain Bellew (an accomplished Oriental scholar, and the talented author of a charming work illustrative of life in India, entitled “Memoirs of a Griffin”), and to mention a few points of resemblance between their own manners and customs and those of their reputed ancestors, which came under my own personal observation.

The features, traditions, and genealogies of the Afghauns (an appellation, by the way, which is not acknowledged by themselves, but has its origin from the Persian language―Pooshtoon being their own name for their country) all tend to prove, though dimly and obscurely, that they are of Israelitish origin, though, whether proceeding directly from the ten tribes which were carried away by Shalmaneser, King of Assyria, and, as we know, remained in the East, or from those Jews who were captives in Babylon, is a point not easy to establish. As it was the kingdom of Israel which was overthrown by the Assyrian Prince, and as the Afghauns call themselves Bin-e-Israueel, I am inclined to adopt the former supposition, though in opposition to it I may state, that one of their traditions represents them to be the descendants of Afghauna, the cousin of Solomon’s prime minister, Asof, whose posterity withdrew, after the Babylonish captivity, some to the mountains of Ghore, Afghaunistaun (within the borders of the Paroparmisan range), and some to Mecca, in Arabia. (It is strange, however, that they should trace their origin to Afghauna, and yet disown the name of Afghaun.) But ready as they are to admit their Hebrew lineage, beware of applying to them the name of Yahoodee, or Jew, an appellation they would deem the deadliest insult, for they hold the more modern Jew, and those who still retain the faith of Abraham, in utter contempt and abhorrence. This may arise from one of two causes: either from their being the descendants of those who crucified the Saviour Jesus Christ, whom as a great prophet, and (as they affirm) the foreteller of Mahommed the Paraclete, or Comforter, they greatly venerate, calling him “Huzrut Esau” (Jesus the most high and exalted); or, which is still more probable, from the fact that many of the Jews of Mecca were stout opponents to the rising creed of Islaum, and bitter enemies of its founder. The tradition of this last may have disappeared, though the hatred based upon it have survived. The language of the Afghauns differs essentially from that of the nations around, and is called Pooshtoon; hence, probably, is derived Patān, the name by which they are known in India. There are strong grounds also for believing that the Pooshtoo is the name borne by one of the ancient dialects of the Syriac language. Many of the singular observances peculiar to the patriarchal ages described in the sacred writings were common among these would be veritable offshoots of the long-lost, oft-found, but still-required ten tribes of Israel. Their pastoral habits were the same as those described in Scripture as belonging to Abraham and his descendants. Unmuzzled oxen tread out the grain from the corn. They glory in pedigrees; and if you ask a man whose son he is, he counts on his fingers the family descent straight up to Noah, to the tomb of whose father Lamech, by the way, in the vicinity of Jellulabad, they resort as a favourite place of pilgrimage. The younger taking the elder brother’s widow to wife, in accordance with the law of Moses, is a custom also observed by them. In corroboration of the same, I give Dost Mahommed Khaun’s own words during a conversation between Sir A. Burnes and himself on the subject of the Afghauns’ descent. (See Burnes’ Travels to Caubul in 1836-8.) “Why, we marry a brother’s wife, and give a daughter no inheritance: are we not, therefore, of the children of Israel?”

The Afghauns stone to death for blasphemy. People guilty of this impiety towards the Prophet are taken outside the Bala Hissaur, to a mound on the Shauh’s meadow, where a Jew lately suffered for blaspheming the name of Jesus. The Afghauns believe Noah’s Ark rested during the Deluge on a high hill in the Koonnur range, north of Jelluabad, and the highest peak of the Soolimaun mountains near the Suffaid Koh (White mountain, from its being covered with perpetual snow), they call “Tukt-i-Soolimaun” (Solomon’s throne).

[Keywords]

qalandan/ yahudi/ naqqara khana/ Qandahar/ charsu/ Shah Shuja‘/ Jalalabad/ Farangi/ masjid/ Qur’an/ kotul-e murcha/ Herat/ Akram Khan/ Timur/ Bani Isra’il/ Pashtun/ Hazrat ‘Isa/ Islam/ Amir Dust Muhammad Khan/ Safid Koh/ Takht-e Soleman

|

NEXT

NEXT |

|

|

BACK

BACK |

|

|