|

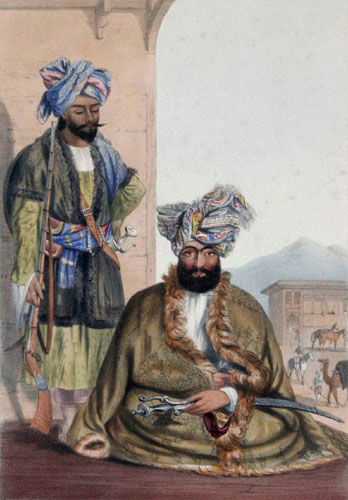

25.GOOL MAHOMMED KHAUN, THE HEREDITARY KING OF THE GHILJYES. 25.GOOL MAHOMMED KHAUN, THE HEREDITARY KING OF THE GHILJYES.

IN April, 1841, our little camp, consisting of my greatly-regretted friend, Captain Bellew, Quartermaster-General’s department (who fell during the murderous retreat from Caubul in January, 1842), and myself, with an escort of Jaunbauz (players with life) cavalry, had reached Chuppa Khāna, thirty miles from Ghuznee, in the western Ghiljye country, on our way to Candahar, when we heard that the whole of the Ghiljyes were up in arms, so that a further advance was impossible. Gool Mahommed (the rose of Mahommed), or “the Gooroo,” as he was called, had again raised the green standard of the Prophet, and to the sound of the “nakarrah” (war-drum) had assembled his wild clan. He was a chief who had been waging perpetual war with us ever since the taking of Ghuznee by Lord Keane, where he joined Dost Mahommed’s eldest son, Mahommed Ufzul Khaun, with two thousand men, and harassed the flank and rear-guard of our army, and attacked the camp itself of the Shauh, his inveterate foe and rival. His object now was to waylay our troops, who were en route from Candahar to take possession of and fortify Kelaut i Ghiljye, a famous stronghold of the Ghiljyes, and a bone of constant contention among them. This being the state of the country we were to pass through, our only guard being composed of these same gentry (Ghiljyes), we resolved to return for the present to our hospitable friends, the officers of the 16th Bengal Grenadiers, at Ghuznee. The kindness with which this fine regiment treated the wayfarer, receiving him at their mess, placing their houses and every comfort they possessed at his disposal, was proverbial through the whole campaign, and will be remembered by all, more particularly myself, with the liveliest gratitude. Before retrograding, however, we inquired of our escort, and the neighbouring chiefs, who came in to make their salāms to us, if they could convey us in safety through the troubled country that lay between us and Candahar. “Bulla”(yes), said they; “be sir-e-chushm” (by our head and eyes), “we will make arrangements.” Our tent all that day was filled to suffocation with chiefs, who, after making various sage propositions for our safety, and extensive demands on our purses, agreed that we were to disguise ourselves as women, in veils, and “boorkahs” (a loose white sack which envelopes the whole figure), and in this way be passed through the Ghiljye camp by one of the chiefs, as his wives. In order to keep up the character of better-halves, we great fellows of six feet to six feet three were to be well doubled up in the “kudjauwas” of his barum (hampers slung on camels, in which the women are concealed from view by thick curtains), and to be delivered to our own people safely, if we survived the jolting, suffocating, breakneck journey of a hundred and thirty-two miles, in the most intense heat, and were not betrayed to our enemies, to be reserved for some grand “kutle-roz” (day of slaughter). These suggestions for our safety delighted us greatly, and we could scarcely listen to our ingenious friends with grave faces, as we thought of the figures we should look with our bearded countenances and lady-like apparel, when dragged out of our hiding-places for the inspection of some Ghiljye admirer of the fair sex. We declined the masquerade, and returned to Ghuznee in safety.

Soon we heard that Gool Mahommed had had a fight; for on hearing of the Candahar advance he hastened out of Kelaut i Ghiljye, and met Colonel Wymer and his handful of soldiers at Asseea i Ilmee, thirty miles from thence. The enemy’s force, amounting at one time to five thousand cavalry and footmen, were opposed to two guns, twenty Sappers and Miners, a wing of Leeson’s Cavalry, and four hundred bayonets of 38th Bengal Light Infantry. The Ghiljyes came suddenly in the night on our party, who formed to receive them, as they rushed on the bayonets with most determined spirit, brandishing their swords and long knives, and yelling fiercely. Again and again they were driven back, again to close with the cold steel, and were at last dispersed with immense slaughter, but not until they succeeded in turning our flank. This engagement lasted five hours, and though the enemy were engaged in carrying off their killed and wounded the whole night, the dawn discovered eighty dead on the field of this unequal contest. Every movement on this occasion was made with the greatest steadiness, the officers and men behaving with that courage and gallantry in which they can be exceeded by no army in the world. The Gooroo thought so too, and as the Ghiljye power was completely prostrated by this and previous reverses, he broke up his army, and naming a place in the mountains for an interview with us, made honourable terms and surrendered himself. The Ghiljyes, in ancient times, were the most celebrated of all the Afghaun tribes. They not only conquered Persia, “the centre of the universe.” but placed their own monarchs on the throne, which they lost only after a long struggle. The representatives of this royal branch was Abdooreheem (grandfather of the Gooroo), whom they crowned in 1800. They then made vigorous efforts to place this descendant of their kings on the throne of Caubul, in opposition to their rival tribe the Douraunees, which gives a Suddozye as sovereign to Afghaunistaun. Led by Abdooreheem, they met the Douraunees constantly in the field, whom they routed in several engagements, but were in turn entirely defeated themselves in subsequent encounters. Since 1802 they remained apparently satisfied with the kind treatment they received from their rivals, until we entered their country in 1839. Thereupon they joined the common cause to exterminate the unbelieving intruders.

After so successfully evading the thousand dangers of the battle-field, Gool Mahommed Khaun, on the evening of his submission, narrowly escaped being slain in cold blood by the single blade of a midnight assassin, who stealing, as he thought, into the tent of the officer in charge of our fallen warrior with intent to murder him, stayed his hand just in time to discover, by the light of a lamp, that his knife was at the throat of his own slumbering chieftain. Being afterwards ordered from Ghuznee to Caubul, I had the good fortune to receive an introduction to “the Gooroo” himself, from Sir Alexander Burnes, who with his usual kindness and consideration granted me this favour (the latest he was spared, alas! to confer on me) on September 29th, 1841. He fell on the 3rd of November, a little more than a month afterwards. On paying the chieftain a visit, I found him lodged with a few of his most faithful adherents, at a karwaunsarae, in one of the Caubul bazaars, a prisoner of state on his parole. Several officers who were at the first taking of Ghuznee recognized in him the chief who led the army that harassed their rear-guard on that occasion. They described him as being always a conspicuous object in the fight, his broad banner accompanying him from rank to rank, and the great men of his tribe rallying round it. On being interrogated, he owned they were correct in the position he took up on that day. On my entering the court-yard of the karwaunsarae, I found it crowded with camels, mules, and horses, tethered in rows by head and heel ropes, heaps of baggage, arms of defence, green and dry fodder, and circles of muleteers, horsekeepers, and “Caufila Baushees” (heads of the Cafila), cooking and smoking, or tending their cattle, signals of the near vicinity of some one of importance. As I ascended the rickety staircase leading to the room of the man at whose name and approach so many had trembled, I naturally felt a degree of anxiety steal over me. How surprised then was I, on being ushered into his presence without ceremony, to find him a simple-mannered person of unassuming appearance, without the least show of importance! Far otherwise: his chamber was bare, and totally unfurnished; his followers the wildest, most savage-looking bandits I ever met with. Stretching out their huge half-naked limbs at full length on the floor, they squatted or lay around on their woolen numdahs in every conceivable attitude. Their arms, consisting of leather shields, long knives, blunderbusses, crooked swords, and matchlocks, hung above them in groups from the rude wooden partitions of the room. In their centre sat Gool Mahommed on his quilt, his arms also hanging above his pillow. They were of the commonest description. He rose and welcomed me most warmly, his vassals scowling at me the meantime, as we chatted together by means of an interpreter. He was a man of dark tawny complexion, which was relieved by a rich lilac Cashmere shawl head-dress, which he informed me was a portion of the “khellut,” or dress of honour, in which he was clothed by the Envoy on tendering his submission. (Nothing would induce him to make his bow to the Shauh; he said he was his enemy, and as a king himself he would meet him only as an equal.) His turban was folded so low down his forehead as to press on his dark bushy eyebrows, which meeting in their centre descended to the bridge of his nose. From beneath peered a pair of brilliant hazel eyes, and a constant grin displayed a row of beautiful teeth to the best advantage. His cheeks, lips, and chin were covered with a close-sitting jet-black curling beard. He was rolled up in the national winter dress (the posteen), an immense cloak of tanned sheepskin with long arms, the woolly side of which is usually worn next the body, the outer leather being beautifully embroidered in many-coloured silks. He spoke of our kindness to him in his fallen state with gratitude, and seemed contented with his changed condition. In proof of this I may mention, that on regaining his liberty at the hands of the blood-stained mob who joined in the massacre of our troops, he took no part against us in our misfortunes, but retired to his own mountains! After taking his likeness, I gave him a penknife, pencil, paper, and India-rubber, and taught him how to use each. It was curious to see the looks of the astonished Ghiljyes, as they roused themselves from their lairs, on his calling them around him to see with what rapidity and ease he could scrawl lines and rub them out. “Ajeeb! ajeeeb!” (wonderful! wonderful!) ran from lip to lip, as they laughed heartily at the miracle. I presented him also with the painting of a young and pretty girl writing a love-letter, which enchanted him; and on his asking if all my country-women were equally beautiful, I astonished him still more by answering stoutly in the affirmative.

On the day following he returned my visit at my brother’s quarters in the 13th Light Infantry lines. We regaled him with tea, to which he insisted on adding milk, as everything, he said, must be “be doostoor Angraisee” (in the English fashion). He wrote his name in Persian under his portrait, and we parted much pleased with this stout, good-natured, honest specimen of a Ghiljye soldier.

[Keywords]

burq`a/ kajawa/ karwansaray/ qafela-bashi/ Gul Muhammad Khan Gilzay/ Kabul/ Janbaz/ Chapa Khana/ Ghazni/ Qandahar/ Guru/ naqqara/ Dust Muhammad/ Muhammad Afzal Khan/ Qalat-e-Ghilzay / Asiya-e ‘Elmi/ Sadozay/ ‘Abd al-Rahim/ Durrani/ Khil‘at

|

NEXT

NEXT |

|

|

BACK

BACK |

|

|