|

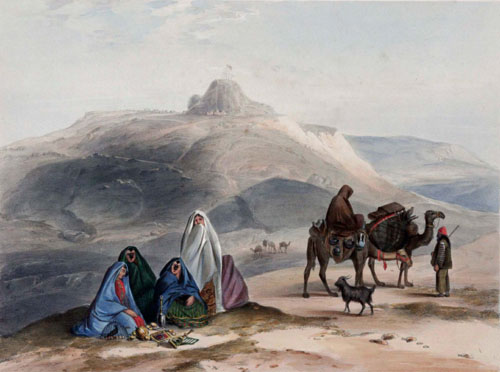

8. FORTRESS OF KELAUT I GHILJYE, AFTER ITS DESTRUCTION BY THE BRITISH TROOPS.

On a rugged eminence between Ghuznee and Candahar, eighty-one miles from the latter city, on the high road to Caubul, rises Kelaut i Ghiljye, borrowing its strength and importance more from its natural position than any defences we found it possessed of on our first occupation of it; though at the time it was a stronghold exciting the utmost show of jealousy from the Ghiljye leaders against the fortunate chief who held it. Far distant from any other station, exposed to sharp and piercing winds, and visited by terrible sand-storms – surrounded as far as the eye could reach by bare precipices, tremendous defiles and ravines, heaped together in the most chaotic confusion, like the giant breakers of a winter ocean suddenly frozen in their terrific course, and fenced round by lofty belts of mountains, all smitten with the curse of barrenness, Kelaut i Ghiljye was by no means an agreeable cantonment. Its garrison, at the time I write of, consisted of Capt. Craigie’s regiment of Shauh’s infantry, six hundred bayonets, two hundred and fifty men of the 43rd Bengal Light Infantry, forty artillerymen, and sixty sappers and miners, which, though so small in numbers, showed itself as right gallant a force as ever climbed the Afghaun mountains. For a space of six month they, like their brethren of Candahar, were cut off from all communication with other garrisons, hearing only from the Ghiljyes, who summoned them to surrender, and whom they afterwards so signally defeated in May, 1842, of the frightful Caubul disasters.

In November, 1841, Craigie marched into quarters, and found the fortifications little more than commenced on, a hundred yards of the works being without wall or ditch. On hearing of the fall of Caubul and Ghuznee, his officers and men began in good earnest to strengthen the defences, until the snow and frost came on and stopped their works. During their tedious winter they suffered extremely from the severity of the weather. The thermometer was forty degrees below freezing, with neither doors nor windows to their barracks, a scanty supply of fuel, the native soldiery on three-quarter rations, and the officers and artillery on bread and water for weeks together.

In the beginning of December they were visited by fifteen hundred Ghiljyes, but the deep snow made them soon sheer off. When the spring broke upon this lonely spot, the garrison laboured anew on the defences, for with it arrived the chiefs, and with them the two great Ghiljye tribes of the neighborhood. They brought at first only a few hundred men, and quartered themselves at a safe distance from the walls, but as April opened they received daily accessions to their strength. Thereupon their boldness increased, until they diminished their distance to less than a mile from the fort. As they approached nearer among the ravines, which were favourable to their skulking mode of warfare, the garrison were obliged to confine themselves within their defences. These, from continual labour, had become very respectable, and such as they deemed no Afghaun would have attempted without guns. In this, however, they were agreeably disappointed. The enemy now completely surrounded them in their trenches, which they had been digging for some days. The nearest were two hundred and fifty yards from the walls, and all loopholed and constructed with skill as to their position, the advanced ones being protected by others in their rear, and placed so as to have the fullest advantage of any natural cover afforded by the ground. From these trenches the hottest fire was poured upon any one exposing himself, evidently by picked marksmen, who threw balls with the greatest accuracy from their long juzzails at seven hundred yards. The Ghiljyes were thus so completely sheltered that the besieged had rarely an opportunity of using their rifles, except when the parties were relieving each in the trenches, but it was seldom that any got into the nearest ones without running the gauntlet of a few double barrels. On the evening of the 20th of May the enemy were so unusually quiet, that it was thought they had decamped, but by means of telescopes the rascals were seen practising escalading at a distant fort – the first intimation we had received of their having constructed any ladders for that purpose. The night was moonlight, and it passed away in the same unusual quiet; but towards morning, just as the moon went down, the clatter of cavalry was heard by the officer on duty, and soon the whole northen face of the works was assaulted by dense bodies of the Ghiljyes. It was so dark that they were not observed, thought every one was on the look out, till they were within a hundred yards. Then they were seen rushing on most boldly, with shouts of Allah, Allah! They were received with so hot a fire that it must have told terribly among their dense masses. They, however, pressed on, pushing their attack with the greatest vehemence at the angles of the works, where the ascent was easiest. By the aid of scaling-ladders they crossed the ditch at the north-east angle, ascended the scarp of eight feet, and a sloping bank of eight more between the top of the scarp and the parapet, and endeavouring to get over the later (which was constructed of sand bags), were met with bayonet and musket. Thrice they came on, planting a standard near the muzzle of one of the guns (two of which were here in position), and thrice were they driven back; one Ghiljye only succeeded in getting over; he was shot with his foot on the gun axle. So determined were the besiegers in their attempts to creep through the embrazures, and mount over the parapets, that the artillery were obliged to quit their guns and assist the Sepoys in bayoneting them, one of whom was seen to spit four single-handed. Many of the garrison were knocked down and bruised by showers of pebbles, which the Ghiljyes throw with unerring and fatal aim. Altogether they fired but little, for, slinging their matchlocks, they rushed up during the height of the attack knife and scimitar in hand. Their boldness was surprising! Their Caubul successes had inspired them with so much confidence, that their women were actually waiting in the ravines close by to share in the plunder of the garrison. The assault lasted nearly half-an-hour. At day-break they drew off. Till two p. m. they were engaged in dragging their killed and wounded from the ravines. Then two companies were unloosed to unearth them; but this could not be done effectually, as they had still eight hundred cavalry on the field, and the garrison were deficient in this branch. One hundred and four dead bodies were left at the foot of the defences, and their killed, as was ascertained by political information, exceeded four hundred n all. Quantities of Ghuznee magazine cartridges were found on the dead. Computed by themselves the number of assailants was from six to seven thousand, and on the body of the steward of Meer-Allum, chief of the Hotuck Ghiljyes, who furnished a third of the force, the muster-roll of his contingent was found amounting to two thousand men. By sunset of the same day not a Ghiljye was visible.

On the 26th of May the isolated garrison was relieved by a brigade from Candahar, and as we approached the British flag waved proudly over the captured standards from the height of Kelaut i Ghiljye. That was a memorable day; a glorious meeting. Hands were pressed in hands of old brother combatants who had never dared to hope of meeting again. Friends, who had been mourned as dead, or prisoners at Caubul, were found alive, or heard of in health and safety. Each had his hair-breadth escapes to narrate, and his battles “to fight o’er again.” Numberless were the hearty jokes shot at some ancient chum’s expense, till now lost sight of, and warm the congratulations as an old familiar face was recognised in the ranks of either force. Nor in the midst of our temporary joy were our brave, unburied dead, forgotten; many a bitter sigh was uttered, many an earnest prayer expressed, and solemn vow of vengeance interchanged, for the fate of brothers, comrades, and “friends of old affections,” “the voice of whose blood,” like Abel’s, “cried unto us from the ground” of Caubul’s dark abysses. A moment of sunshine like this, though not unalloyed with pain, compensated for many a dreary month’s anxiety and doubt.

After razing the barracks and defences, we returned on 7th June to Candahar, justly proud of the addition to our army of so brave a band as the distinguished Captain, now Major Halkett Craigie, C. B., and his excellent troops, who having fortified and maintained their isolated position in the face of an enemy of great courage and overwhelming force, had at length signally defeated their utmost efforts with a skill and valour that could not be surpassed by the most experienced veterans.

[Keywords]

Qalat-e Gilzay/ Ghazni/ Qandahar/ Mir ‘Alam/ Hotak Gilzay

|

NEXT

NEXT |

|

|

BACK

BACK |

|

|